| |

In a recent tome about philosophical/psychological alternatives propounded

by the major thinkers of history, the author expended thousands of words

in much earnest wringing-of-hands about The Reason For It All. He impressed

me greatly with his conclusion: "there is something fishy about

human existence."

Trawling around

in these murky depths is Robert Heinecken. And what he catches and offers

for our consumption is redolent of fishiness. This is particularly true

in this portfolio, Recto/Verso, in which seemingly random conjunctions

of unpredicatable factors so consistently create recognizable and significant

images.

Now and again others

have landed similar images by a fluke. There was a bit of a flap a few

months ago when a local woman was startled to see Jesus' face emerging

in a frying taco shell. The taco was consecrated, not consumed, and

the image became a shrine to hundreds of pilgrims. And, if I remember

right, Elvis recently appeared in the mold on an old refrigerator. But

my favorite example is an uncited newspaper clipping pinned up over

the Xerox machine in our art department: a likeness of a patron saint

has miraculously appeared on the scrotum of a fifteen-year-old Italian.

(The account included a photograph of the scrotum image, so it must

be true). Pilgrims are flocking to the blessed house, where the boy,

Giuseppi, displays his holy scrotum through a hole in a screen. Giuseppi

is philosophical about God's visitation: "The Lord has picked my

testicles to do his work," he says. "I wish He had picked

my friend Arturo's, but that's life." It sure is. As Woody Allen

said, "…the Cartesian dictum 'I think, therefore I am' might

be better expressed 'Hey, there goes Edna with a saxophone.'" Image

is more interesting than abstraction.

Both Robert and

Giuseppi share a faith in possibilities; the difference between them,

however, is not one of kind but of consistency. Heinecken seems to have

a psychic resonance with such residual images, which become even more

significant because of their frequency and degrees of latency. As he

has said: "I have the feeling that there are things happening that

are really very interesting, if we can somehow find the key that makes

them visible."

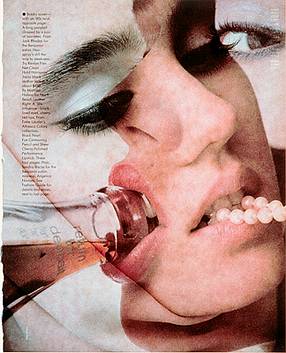

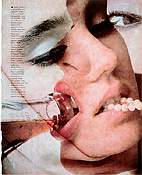

I cannot find an

image of Jesus, Elvis, or even a common saint in the particular Recto/Verso

image assigned to me — but there are plenty of other fishy things

going on. I squint, revolve the page, and all sorts of latent images

are brain developed. There's a squatting nude grinning typographical

teeth, vomiting a sub sandwich (ham and cheese by the look of it) into

a gaping maw with lips pulled apart by a giant's limbs; directing the

flow is a Barbie doll in sunglasses, displaying provocatively enlarged

breasts. A slight turn and there's a voodoo mask chomping on a severed

leg. Turn again, and puckered ruby lips have opened to accept a glowing

cigar butt. A further turn and a graceful swan's head is thrusting its

beak between ivory thighs. And so on…

The "interpretations"

are no less there than the more overt surface manifestations.

As has been already pointed out elsewhere, the title piece of Heinecken's

other, earlier portfolio, Are You Rea, not only includes the

anagrams ARE and REA but also suggests ERA, both for the time in which

we live and the Equal Rights Amendment. There is also the temptation

to complete the word "Rea…" as "Real" or "Ready"

(or even "Reagan"), when the trigger is a woman holding open

her blouse. I can never see this title without associating "You

Rea" with "Eureka," a cry of discovery.

If Robert Heinecken

can dredge these photograms of magazine pages for so many strange, beguiling,

and even meaningful associations and images, the question becomes one

of chance or coincidence. I am referring, of course, to the hoary analogy

of a particularly obsessed monkey eventually typing a Shakespeare play.

Equating the artist with a monkey (even one so tenacious as this) seems

rather insensitive, like Tammy Faye Bakker interviewing an armless woman

on the PTL Club and asking, "Well, how do you put on your makeup?"

I feel justified in posing the above, similarly impertinent question

because I have a point to make which, to me, strikes at the essence

of Recto/Verso.

In order to make

the point I must first introduce a man with the appropriately photographic

name of Kammerer. Paul Kammerer was an Austrian biologist whose professional

passion was the proving of the Lamarckian theory of evolution. (He shot

himself when it was discovered that his prize specimen, the so-called

"midwife toad," had been tampered with to fake the evidence).

Kammerer's avocation had been his conviction that apparent coincidences

are merely tips of an iceberg, which happen to catch our attention.

In other words, he reverses the skeptic's argument that from among myriad

random events we select only those that seem significant. To Kammerer,

"coincidences" are the rule, not the exception. He believed

that there is an as yet undiscovered law which clusters non-causal concurrences

into significant lumps. This, to Kammerer, "is a simple empirical

fact which has to be accepted and which cannot be explained by conicidence

— or rather, which makes coincidence rule to such an extent that

the concept of coincidence itself is negated."

In a beautiful analogy,

Kammerer likened this force to a "cosmic kaleidoscope" that,

in spite of constant shufflings and random rearrangements, also takes

care to bring like and like together — and to create recognizable,

relevant juxtapositions by chance, as in this portfolio.

We may be condemned,

because of our humanness, to play the role of "peeping Toms at

the keyhole of eternity," as Arthur Kosetler says in a similar

analogy, but Robert Heinecken has taken the stuffing out of the hole,

giving us a clearer look at even our limited view. What Heinecken states

as his interest in "residual reality" bears an uncanny resemblance

to Kammerer's "seriality" (and it might be added to Jung's

"synchromicity" and Pauli's "exclusion principle"

and Hardy's "psychic blueprint" and so on). Unfortunately,

such terms sound pretentious as if the idea were too difficult for non-specialists.

As Goethe put is: "When the mind is at sea, a new word provides

a raft." In fact, the principle is simple, if heretical.

What Robert Heinecken

reveals in Recto/Verso is that the explanation of coincidence

just will not wash, that underlying such randomness is a remarkable

symmetry, as if something is trying to tell us something. And that is

not only "bloody fishy," it is also the meaning of art.

|